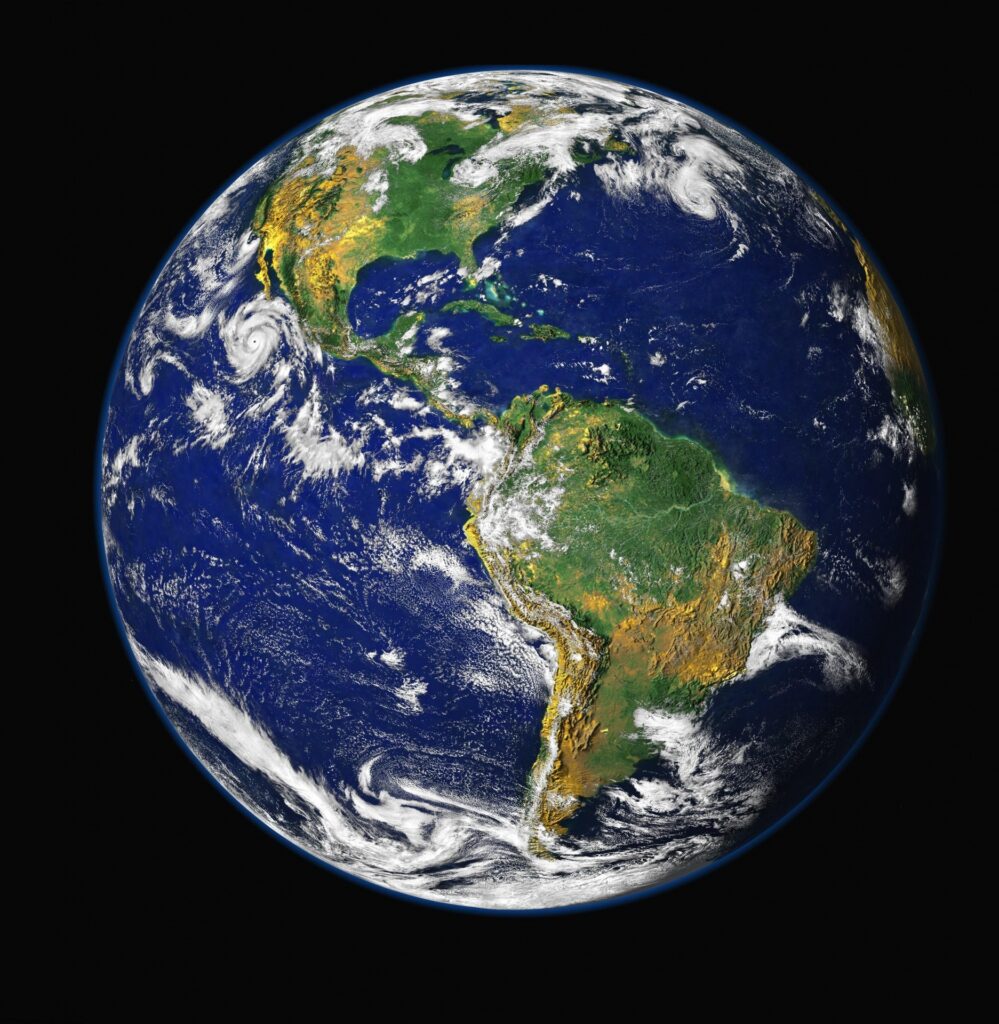

NASA/NOAA/GSFC/Suomi NPP/VIIRS/Norman Kuring / Public Domain

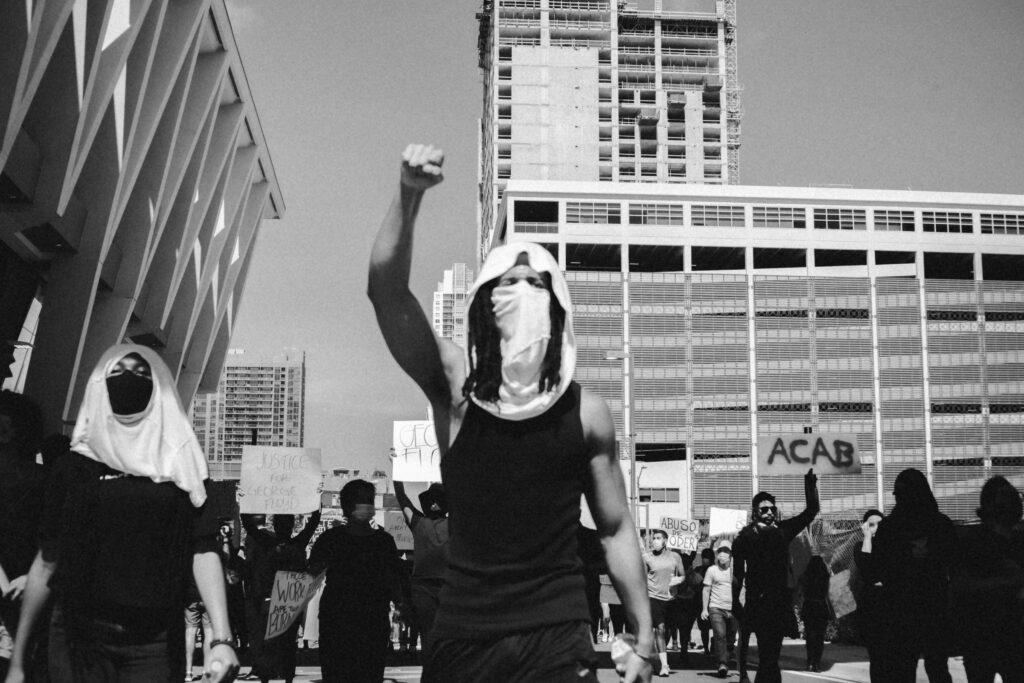

Photo by Frankie Cordoba via Upslash

Author’s Note: Opinions of a Layman on Repression and Resistance, Part I can be found here. The sources which are linked to in the body of the essay are those used in its composition. This essay (as well as Part I) should be understood as a primer on these sources and a jumping off point for further, in-depth reading.

As I periodically check social media for news on the ongoing protest movements across the U.S. (and the world) engaged in the struggle against state violence, I sometimes delve into the comment section of news articles and op-eds to assess what kind of conversations are being had. On a post quoting Desmond Tutu’s declaration that if you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor, one comment out of the many interpreting the quote in bad faith (and generally with no awareness of the privilege inherent in remaining neutral) stuck out to me the most. This young, white male posited that he had bigger concerns, namely environmental concerns. It reiterated just how fragmented our collective understanding of the superstructure’s function and reach is, for he failed to realize that to fight against a power structure that kills and imprisons BIPOC at disproportionate rates is to fight against a power structure that extracts and pollutes carelessly; they are one and the same.

The COVID-19 death toll in the U.S. has climbed to 170,000 deaths and counting. Data is beginning to show the disproportionate infection and mortality burdens that BIPOC populations are shouldering, and as the data grows these disparities and the structural inequalities they point to become harder to ignore. This is yet another instance of the pandemic shining a light on structural problems within society. The increased infection and mortality burden shouldered by BIPOC cannot be adequately explained by genetic differences, instead it is likely the result of a complex of conditions that result in less access to wealth and healthcare which in turn have adverse health outcomes (and not merely in a COVID-19 context), historically the usual culprits in similar situations. This complex of racist and classist conditions includes BIPOC communities living in closer proximity as a result of cramped living conditions, holding a larger proportion of low-paying essential jobs in the service sectors and using public transportation to commute making it harder to socially distance. In many cases these communities, in addition to lacking access to adequate healthcare, must bear the consequences of environmental racism which places their health in a position of vulnerability long before coming in contact with SARS-Cov-2.

Environmental racism can be understood as a complex of socio-economic and environmental injustices (political and real) that result from racial and class inequalities and discrimination. It has many differentiated yet interconnected manifestations on both local and global scales. In this way a diverse set of policies and practices that result in equally diverse outcomes, like the hyperlocal problem of Flint’s ongoing water crisis or the global problem of waste management, can be attributed to systemic racism and classism. We have to remember that deciding where to place a landfill or appropriate a carbon sink is not inherently a racist or classist act, but a racist and classist power structure will always engage in paradigms of uneven development that result in winners and losers along established lines of race and class. Uneven development is not accidental, it is a feature of the capitalist world-ecology.

The rich and powerful create problems for all of us, then tell us we’re to blame.

Jason W. Moore

The Anthropocene is a proposed geological epoch dating to the beginning of Humanity’s increased impact on Nature’s earth systems. As environmental historian Jason W. Moore points out, the Anthropocene conversation is several; there is the conversation within scientific circles as to what constitutes an appropriate “golden spike” (an indication of change) in the stratigraphy, a conversation which in turn flows into the larger academic conversation around the periodization of the Anthropocene: when did it start? The importance of this question goes beyond establishing scientific facts (not the least because science both constrains and is constrained by the thought-structures of the day), but extends to how we conceptualize the relationship between Humanity and Nature and where we place the blame for the ecological degradation that has come to define this relationship.

Moore argues that the Anthropocene as an explanatory narrative is insufficient in articulating how we got to this moment of ecological crisis because it perpetuates the very binaries that underpinned the capitalist colonial project, and as a result is too reductive or incomplete an explanation. The narrative which the Anthropocene offers is one that sees Humanity acting upon Nature to the point of ecological crisis, conceiving Humanity and Nature as two separate parts of a whole. Yet the reality is much messier: humans are part of the web of life, and our institutions while being distinct from their environments are their product (if for no other reason than what Moore calls the ontological condition of geography). Further, the Anthropos to blame for the ecological crisis of this narrative is an undifferentiated monolith, a discourse that flies in the face of environmental research; as Moore puts it, “the rich and powerful create problems for all of us, then tell us we’re to blame.” The Anthropocene as explanation is insufficient because it fails to consider an important factor: Capital, and its role in reshaping ecologies.

As the work of Moore shows, Capital was reshaping ecologies long before any Industrial Revolution or Nuclear Age. The colonial project itself can be understood as one of cataclysmic ecological restructuring, not merely as a result of a Cartesian revolution that redefined the relationship between Humanity and Nature, but as a result of resource exploitation in the colonies which led to large scale mining and deforestation. Colonialism in one sense can be understood as a project to expand the boundaries of the commodity frontier as a result of depleted resource bases back home, a process that was the result of the expansion of specific resource intensive industries, like metallurgy or potash production, often funded by powerful and monopolistic economic interests of the time.

The thing to remember is that this process is not linear: capitalism doesn’t develop in a closed system, it is not the result of merely one set of circumstances. As mining, metallurgy, shipbuilding and other lumber intensive industries advanced, deforestation advanced in parallel as forests, in many cases the commons, were enclosed and made productive. This process of enclosure, whether economically or politically done, dispossessed the commons from those who had historically subsisted on them to the benefit of a minority elite, thereby creating a new working class necessary to sustain industrialization in urban centers. However, it isn’t just enclosure and vagrancy laws that are important conditions in the formation of this new working class; a series of agricultural revolutions during the long sixteenth century meant that less labor was necessary to produce higher agricultural yields, meaning more and more people had to rely on wage work to make a living as the long century progressed.

Colonialism was not just the latest act of dispossession by Capital, it was also the latest reconfiguring of who was part of Humanity and what was considered productive work. The exclusion of Black and Indigenous populations from the category of Humanity justified their exploitation as cheap labor, and the devaluing of child labor and gendered work allowed the contribution of women and children to be devalued even as this labor was integral to the formation of capitalist industrial societies. The shift to a logic of Capital meant wealth was no longer measured by how productive land was, but how productive labor was even if so much of the work required in the maintenance of daily life had to be devalued as work.

The logic of the Anthropocene reproduces the logic that underpins capitalism, for it too is predicated on the Cartesian binary of Humanity/Nature and the premise that Humanity inhabits Society and acts upon Nature (ignoring that Humanity, and by extension Society, are embedded in Nature and in one sense a product of it). This Cartesian logic allows capitalism to reduce the web of life into discrete systems to be managed and exploited, as well as a way of appropriating labor power from populations by reassignment from the category of Human to Nature. In this context racism and sexism (white supremacy and patriarchy) are not just a cultural necessity to divide the working class, but a structural requisite of capitalism to appropriate new sources of cheap labor by a fluid process of othering certain populations. This was after all the logic of chattel slavery, which justified itself morally by denying the humanity of the Slave (chattel, a synonym for personal property, shares etymological origin with cattle).

The Anthropocene as a deficient explanatory narrative of ecological crisis can be a case study for the limits of an environmentalism that does not take seriously the role of Capital (and its logic) in ecological degradation. And this is exactly the problem with green capitalism, and the neoliberal environmentalism it deploys in its quest for sustainable development and a decarbonized global economy. Ultimately, neoliberal environmental policies represent a new form of dispossession and an expanded accumulation frontier. Central to these policies is the belief that free trade and economic growth are not only compatible with environmental sustainability, but important preconditions for finding and deploying the most effective solutions to the current ecological crisis. The neoliberal solution to environmental problems is simply more efficient management of resource exploitation in accordance with natural limits, and the creation of market mechanisms (like cap and trade) to mediate access to ecosystem services and rights to pollute.

Cap and trade is a two part system aimed at reducing greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere by placing a limit on the amount of their emission across an industry or economy and reducing that limit over time. The state sets these limits (or caps) for any given GHG in any given industry and enforces them by giving companies pollution allowances in the form of carbon credits in accordance with these limits and setting fines for violating these limits; companies that are able to limit emission below their allowances can then sell (or trade) their surplus carbon credits in a carbon market. In addition, companies can purchase carbon credits from clean development projects facilitated by the Clean Development Mechanism (or other voluntary markets with similar functions), a market for buying carbon offsets produced by these projects.

Proponents of these market mechanisms believe the market will find the cheapest and most effective ways of cutting emissions. Yet there are numerous case studies that point to this combination of market mechanisms leading to new forms of dispossession and exacerbating environmental degradation instead of mitigating it, as in the case of a CDM biomass power generation project in Thailand that used rice husk as the raw material:

While local industrial elites call this rice husk ‘waste,’ peasants in the area have been using it as natural fertilizer and for brick manufacturing for generations. However, now that profits can be made from burning the rice husk for electricity generation, creating ‘carbon credits’ that can be sold to Northern countries and companies, this renewable technology/ resource has become a valuable (overpriced) commodity. As a result, peasants now have to buy chemical fertilizers, which increase their cost base. This has an indirect impact on climate change, since the production of these fertilizers itself generates carbon emissions. Additionally […] there have been health (e.g. respiratory problems) and environmental hazards (e.g. dumping of waste ash) produced by this new ‘clean development’ project.

In many cases CDM funding subsidises dirty industries in the Global South like coal-fired power plants, paper mills, and dam construction which increase net fossil fuel consumption, because Designated National Authorities (DNAs) neglect their duties as watchdogs.

The problem with neoliberal environmental policy is that it is the result of a political economy that prioritizes maintaining a fossil fuel status quo over actually cutting GHG emissions, leading to ineffectual market mechanisms that far from actually cutting emissions merely create new avenues for profit from already existing dirty projects or dispossess people of land (including for carbon sinks, in a process eerily similar to enclosure) and resources. As Marxist academics have pointed out, including Moore, market mechanisms are “best understood as part of a trajectory of capitalist dynamics structuring human relations to the natural environment in specific ways, while producing and re-producing processes of inequality within and between countries.”

If Branson, a billionaire tycoon, in good faith failed to produce results, then it must be recognized that perhaps capitalism and free market fundamentalism have failed at solving the problem they produced.

If neoliberal environmental politics cannot sufficiently green capitalism to the point of sustainability, that is if capitalism cannot sufficiently transform itself, surely it can transform technology, the planet or both to such a degree as to avert the worst of this ecological crisis? Consider the case study of airline tycoon Richard Branson offered by Naomi Klein: after an epiphany of the dangers of climate change was spurred by a meeting with Al Gore, he announced an initiative to develop green biofuel alternatives by diverting $3 billion of profits from Virgin’s transportation divisions towards their development. If the transportation divisions were not profitable enough profits would be diverted from all Virgin owned businesses. That wasn’t it though, a year after this pledge Branson announced the Virgin Earth Challenge, a competition with a $25 million prize for anyone that could invent a method of sequestering carbon from the atmosphere without harmful counter-effects. He also launched the Carbon War Room, a group of industry insiders looking for ways that polluting sectors can cut their emissions voluntarily and economically. The hope underpinning these initiatives was that the resulting technologies would allow for an unchanged political economy and culture of consumption, for businesses as usual to continue.

Seven years after his $3 billion pledge for biofuel development, that initial goal had already been diluted; Virgin Fuels became the Virgin Green Fund, a private equity firm invested in a diverse portfolio of green and green-ish technologies and one biofuel. The $3 billion pledge has become a $300 million gesture towards sustainability, as a result of profit shortfalls from his transportation divisions, profit shortfalls that did not however affect Virgin’s ability to expand its airline operations and put more carbon in the air. The Earth Prize remains unclaimed, as none of the thousands of applicants pitched technologies that could sequester carbon at the scale necessary while being financially viable and profitable. In time it too changed from an initiative to find viable carbon sequestering and storage technologies to an initiative to find carbon sequestering and recycling technologies that would transform sequestered carbon into a valuable commodity. This commodity can then be used as a source for carbon intensive methods of fossil fuel extraction, increasing the system wide output of GHG even if one aspect of that system sequesters carbon.

A cynical analysis of this case study would lead one to conclude that these green initiatives on Branson’s part were just a way of managing PR as he prepared to expand his fossil fuel intensive operations at a time when climate scientists and advocates are calling for their wholesale reduction on a global scale. Even a more charitable analysis has to conclude that if Branson, a billionaire tycoon, undertook these initiatives in good faith and failed to produce results, then it must be recognized that perhaps capitalism and free market fundamentalism have failed at solving the problem they produced.

Other technological fixes centered around large scale manipulations of earth systems, including ocean fertilization and multiple methods of Solar Radiation Management (SRM or sun dimming), are not mature enough to deploy safely. The idea that we can geoengineer our way out of this ecological crisis is an extension of the very logic that got us here: the belief that ecological systems can be managed efficiently and effectively, that we can bend them to our will. To think that we can change an aspect of the system without irrevocably changing it as a whole betrays our lack of understanding that the ecology is a dialectical system which responds in real time to our actions, it is not closed or static. Further, computer modeling shows that these SRM technologies under certain conditions (such as the release of sulfur into the upper atmosphere from locations in the northern hemisphere) could result in decreased rainfall in regions of Africa and Asia resulting in the collapse of their food systems and famine.

Proponents of geoengineering argue that these models are not infallible especially when predicting regional outcomes, and so these negative externalities are not a given. But what this means is that institutions and individuals in the Global North are demanding that marginalized populations everywhere (but especially the Global South) bear the brunt of the consequences of large scale geoengineering even when we do not know what these consequences might be, all so that a relatively small proportion of the world population can keep accumulating wealth from unchecked fossil fuel consumption. In this light, geoengineering would constitute another iteration of the uneven development to be found in a capitalist world-ecology, and which is often racialized and gendered. In other words, the latest iteration of environmental racism.

On a material, day to day level, because life is short and singular, I don’t particularly care if the solution is green-Keynesian capitalism or communism that saves us.

Ultimately, the anti-racist struggle and the environmentalist struggle must become part of a broader coalition of intersectional struggles under an anti-capitalist banner. If the superstructure is classist, racist, sexist and any number of other -isms that can be used to describe it, it is so as a reflection of its function, which is to restructure the world-ecology from a web of interconnected and interdependent life into discrete categories for commodification. Nothing is exempt from capitalism’s appetite, and nothing is held in high enough esteem to abnegate this appetite.

Of relevance, the state apparatus killing and incarcerating BIPOC disproportionately and violently repressing protesters is the same state apparatus violently repressing environmentalists and protecting the private property of extractive industries everywhere around the world. This is the same state apparatus that has become a node of rape culture. The same state apparatus that harrassses the homeless and enforces evictions against the working class. We must recognize that the power structure benefits from fragmenting our common struggle so that we cannot take aim at it for the common enemy that it is.

We must engage in a project of transformative environmentalism. One which on an ideological level seeks to rearticulate our dualistic conception of nature and our relation to it into a more profound understanding that we are part of the ecology, not outside of it; and which on a material level seeks to dismantle the neoliberal institutions (and the policies they prescribe) created to simply manage natural resources for more sustainable exploitation enabled by this dualism, replacing it instead with a patchwork of local stakeholders engaged in the stewardship of whole ecosystems through a combination of traditional ecological knowledge and scientific knowledge.

However, the scale of our environmentalism and our conception of what exactly constitutes environmentalist action must expand. If we understand capitalism for the world-ecology that it is we come to realize that to be environmentalist requires one to be anti-capitalist. In this context the most viable way out of our ecological quagmire, sustainable degrowth of the world economy, can be understood as environmentalist in nature. The emphasis of course is on sustainable, implying that this process of degrowth would not result in social regression or stagnation (as human progress would simply continue along a more holistic trajectory), or the negative externalities of the forced degrowth we have come to expect every time a bubble bursts, every time a boom goes bust. This means the way and amount in which we produce and consume commodities, and as a result the way we live, must change wholly. The good news, as Klein points out, is that in reconfiguring the way in which we live and sustain ourselves we can create a more equitable and just world in the process.

Imagine how much more resilient an economy in equilibrium with the web of life from which it emerges, and which prioritizes the health and quality of life of communities over wealth accumulation, would be in the face of the current global pandemic. The pandemic was a shock to the system that resulted in unsustainable degrowth of the economy as social distancing measures went into place to flatten the curve. But while the pandemic triggered a recession that greatly affected the working class, capitalism adds flames to the already roaring fire in the form of artificial scarcity (making the recent condemnation of looters in this context even more absurd).

The neoliberal project of a techno-managerial, market based approach to solving the climate crisis has been a resounding failure; in fact, it can be argued has only made things worse. Deregulation, another neoliberal project funded by corporations involved in extractivist industries (the very corporations that similarly stand in the way of developing and promoting green energy infrastructure), has similarly proved disastrous for the environment. What’s more, philanthropic millionaires and billionaires will not save us, as they will always put their short-term corporate profits over the long-term wellbeing of our planetary systems, choosing to take token action for the sake of optics. Thus, it becomes apparent that to protect the environment we must adopt an anti-capitalist position that is truly environmentalist in the way it prioritizes the ecology over free-market fundamentalism.

On a material, day to day level, because life is short and singular, I don’t particularly care if the solution is green-Keynesian capitalism or communism that saves us. The reason I’m so anti-capitalist is that fundamentally capitalist political economy, predicated on continual expansion both as material requisite and as ideology of accumulation, is incompatible with the hard limits of reality and will always result in metabolic rifts that lead to crash-boom cycles, the big final crash always being kept at bay by ever more draconian economic policy and serendipitous technological shifts. Capitalism will always cannibalize itself, and devours us all in the process.