I had sensed that our relationship was changing even before we left California, like a premonition glimpsed in the stirring of leaves or in a reflection caught between ripples. I was mourning a death that had not yet occurred, and whenever I turned to look at him it was like staring at a stranger. As I write, trying to make sense of where I went wrong, what words I spoke that I should have left unspoken, I am left with the sense some vital piece is missing. What I remember most vividly about our last conversation was the look of quiet desperation in his eyes which at the time I interpreted as frustration at his inability to articulate himself, but was probably, I understand now, a silent plea for me to stop. I never got a chance to thank him.

By the time this novel coronavirus had made its way across the globe and social distancing became the new normal, I had already been living like a ghost in Bangor, Maine for a little over two months. We arrived in Bangor on January 20th after a week of hauling ass across the United States.

I had spent a week here the summer before just as it was ending, and the days were getting shorter. Then it had felt like a foreign place, an unknown country. My days had the quality of a last meal, perhaps because I had come all this way to accompany Heather, my significant other, who I would be leaving behind to pursue her graduate studies. I would join her some months later.

The first few days back were the loneliest. They were short, frigid days which collapsed into each other like an existential pileup of time and space, the kind that leaves you confused about your whereabouts even as you fail to get out of bed. I did not know anyone here and made little effort to meet anyone. I seldom left my apartment.

Photography allowed me a physical intimacy with this new place I call home as an unintended consequence of my aimless excursions through the surrounding neighborhoods, both in search of photographs and an interruption to the quiet monotony of my first Maine winter (and later quarantine). It is easy to love a city and not know it, to live in a city and only know a fraction of it. You stroll through familiar streets tracing epicycles of routine that render portions of the city invisible to you because of a kind of existential parallax. Photography allowed me to escape the routine of daily commutes; deviations that revealed new aspects of the city on each outing.

In this way I began to understand the geography of my new home, and landmarks began to emerge in the landscape from the ephemera of suburban life such that I could orient myself thanks to the pair of red plastic lawn chairs in the front yard of this house or the Trump 2020 sign planted askew in the lawn of that house. I became familiar with street names, and these helped too. Little by little the labyrinthine geometry of my new hometown came to make sense, though at times I felt no less dislocated.

I quickly learned to read the everyday minefield of a frozen sidewalk or an unplowed street after a snowfall. I began to differentiate between kinds of snow. I got used to the bitter cold of winter which Mainers liked to remind me any chance they got was only bitter and cold by Californian standards, but in fact was relatively mild by Maine standards. What photography couldn’t do, not immediately anyway, was help me assimilate into the culture of the place. I realized this would take more time, and some effort on my part.

I started reaching out to local farmers, grocers, chefs and restaurants hoping to integrate myself into the local food scene and create a collaborative network of local craftspeople and artisans. I would source my food and other consumables through this network all the while documenting different aspects of this process with a variety of end goals in mind for this work. I wanted my short time in Bangor to be meaningful regardless.

I did not expect the extent to which the University of Maine would become a daily presence in my life, at least in those first few weeks. It began with an invitation to deliver two small lectures on screenwriting and film production to an underclass studying depictions of anthropological and archeological subjects in Hollywood cinema. Then my partner got word that her thesis would involve traveling to the coast of Peru to compile ethnographies of two different coastal communities, including the artisanal fishermen of Huanchaco. She would be doing this work in the summer, and I would accompany her as her documentarian. Later the opportunity arose to extend our stay in Peru as volunteers on an archeological project in Chachapoya.

All this was short-lived as the evolving pandemic brought many of these plans to a screeching halt. Sometimes my belly feels like it will open up into a blackhole that swallows me whole, and I cannot tell if that is just a general anxiety or my body succumbing to SARS-Cov-2. I assume it is just anxiety and take a few deep breaths.

I met a Peruvian writer at a dinner with Peruvian academics after a lecture on ritual human sacrifice, one night. He was a real writer I realized, not like what I do (Capote would call it typing). Dan, our host, mentioned every work he had produced, by genre not by title, as if he were going down a checklist the totality of which would qualify one as a writer. There was a novel, a volume of poetry, and several pieces of literary criticism, all of which culminated in tenure within the Spanish department at the University of Maine, Orono. You could say that when it came to making a career out of writing he had really crossed his t’s and dotted his i’s, while I could hardly place a comma in the correct place. He told me from across the table that we should go out one day. I smiled and agreed, but forgot to get his number, and now I may never. He lives two floors below me. Thank god for silver linings.

As daily life became altered by the pandemic, I expected the subject matter of my photography to change as well. But I have struggled to capture the pandemic, to capture the banal terror and paranoia. Of course, the subject matter of my photography has changed, as a result of social distancing measures, but in ways I didn’t expect. I have found a new love for food photography and styling. Perhaps more meaningfully for my body of work, I have begun to point the camera inwards, towards my own domestic life. And I’ve come to realize that this is its own implicit record of the pandemic, or an aspect of it.

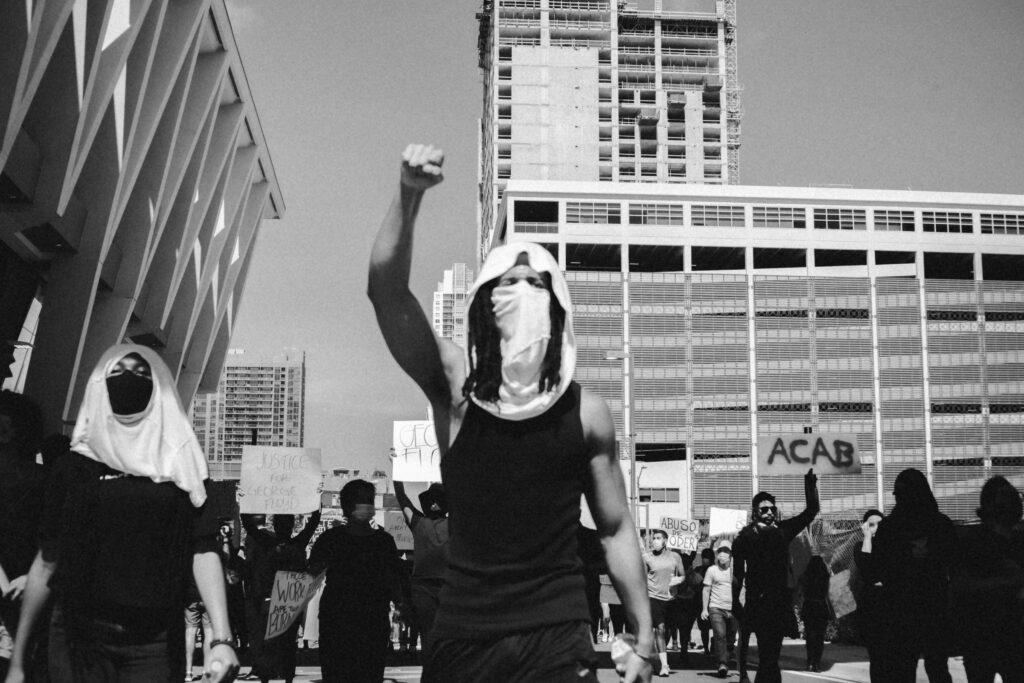

This has to be enough, for now at least. Vacationland seems unchanged, if mildly inconvenienced, by the pandemic or the protests against state violence that have erupted globally. Our hospitals have not been overwhelmed by infections, our residents have not been tear gassed by their own state. There was a relatively small local gathering in a show of solidarity, which I could not attend.

In a way it felt like self-imposed exile; after all I had come here of my own free will. While others were witness to history, I was witness to boredom and nostalgia and melancholy; in short my own solipsistic mood. At least that’s how it felt, anyway. If photography is a language, I lack the words and syntax to capture this pandemic. To do so requires the touch of a poet, not of a gossip; a whisper, not a shout.

I realize I’ve never taken a portrait of my father or my mother, not like I’ve taken of brides or street vendors or other strangers. I can’t imagine reducing my father to a single image, I just don’t know the man well enough. Sometimes when I am alone and overcome with sadness and anger, I think about him. I remember evenings when he would come home smelling like earth, when he would wash away the sweat and soil with Head & Shoulders before leaving for the night shift at the AMPM. I imagine him in his polyester work shirt, standing alone at the register in the dead of night, and I wonder what he felt. If he ever got bored, or thought of running away? I wonder if he ever looked at my infant face, and felt pangs of regret.

My mother on the other hand, I can see her seated next to my grandmother: the two are in my grandmother’s kitchen, engaged in some sort of food preparation as the midday sun floods in through the skylight above them. I wonder when and if I’ll get to capture that moment. That image of my mother is no less reductive, but it captures a vignette I’ve experienced many times before and hope to witness at least once more. I negotiate with the universe for the smallest kindness during times like these, the way you might beg an executioner for a final look at the sky before the hood is pulled over your head. The pandemic seems to have exploded the dimensions of distance; I pity separated lovers who must feel like ants on the surface of an inflating balloon.

What I have lost by growing up in the U.S. is an urgency towards family. A loyalty and concern for family certainly still exists but in an untethered state; I am a comet tracing a parabolic orbit around them, returning every once in a great while out of habit and sheer inertia. I wonder if I’ll feel like this upon their death, even if some part of me already knows that it will ultimately all turn to guilt and regret.

He tried to tell me something in my dreams, but even then he could not speak. I used to think you could know yourself completely, achieve total self-awareness. Now I think there is always some part of you that you cannot know, a kernel of terra incognita that might get smaller and smaller as the years go by but never disappears; a sliver of yourself which you cannot see and will never see because of a kind of existential parallax that always keeps what’s behind your head hidden no matter how quickly you try to turn and see the ghost that walks with you.

One night, during one of the last snowstorms of the winter, I walk out to an empty and dark parking lot. It has been freshly plowed but already the tracks of the snowplow are disappearing. There is nothing but snow and blackout as far as I can see in all directions, and this doesn’t change when I get on the road, my headlights the only visible light except for the occasional car passing me in the opposite direction blinking in and out of existence. The snow falls in big clumps of snowflakes. At a traffic light I get tired of waiting for the light to change and I run a red light, but there is no one to witness my trespass. As I drive on, I imagine the whole world buried under mountains of snow, but by the next morning much of it has already melted, and you can see soggy cigarette butts poke through and the cracks in the sidewalk beneath.